Welcome.

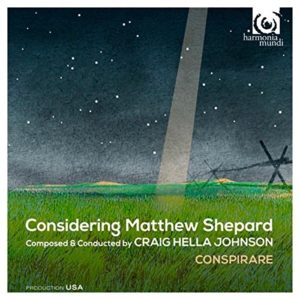

Thank you for being here for this world premiere of Craig Hella Johnson’s oratorio, Considering Matthew Shepard.

Let’s imagine that we are in a church in Italy where we are about to hear one of the early oratorios. The year is 1619. Giovanni Anerio, a composer who three years earlier had become a priest, is presenting his Conversion of St. Paul: Saul travels down a road, sees a great light, hears a voice, is knocked down, gets up blind, goes on to Damascus where his sight is restored after prayers. Saul the persecutor becomes Paul the Apostle.

In this oratory there are four soloists: a narrator called Historicus, St. Paul, a Voice from Heaven, and Ananias of Damascus, a disciple of Jesus. There is also a four-part chorus that sing the words of the people in the street.

At least by 1624 there were also secular oratorios. Monteverdi composed the oratorio Tancredi & Clorinda, a romance of attraction and conflict between a Christian knight and a beautiful Muslim warrior woman, set against the backdrop of the First Crusade.

Over the centuries, the musical composition form of the oratorio evolved. One of the most popular oratorio forms was the Passion Oratorio, a composition focusing on the suffering and death of Christ, often performed during Holy Week. When Johann Sebastian Bach becomes musical director and cantor at St. Thomas in Leipzig in 1723, he adds his own genius to the passion oratorio form. (Some of us will likely be listening to Bach’s St. John Passion or his St. Matthew’s Passion over the next few weeks.) Bach stretches the oratorio form, emphasizing the operatic aria, increasing the significant of the chorale or hymn, adding sections designed to provide time during the oratorio for contemplation and reflection. He uses the narrative (or narrator) prominently as a framework. He composed opening and closing choruses.

Over the centuries, the musical composition form of the oratorio evolved. One of the most popular oratorio forms was the Passion Oratorio, a composition focusing on the suffering and death of Christ, often performed during Holy Week. When Johann Sebastian Bach becomes musical director and cantor at St. Thomas in Leipzig in 1723, he adds his own genius to the passion oratorio form. (Some of us will likely be listening to Bach’s St. John Passion or his St. Matthew’s Passion over the next few weeks.) Bach stretches the oratorio form, emphasizing the operatic aria, increasing the significant of the chorale or hymn, adding sections designed to provide time during the oratorio for contemplation and reflection. He uses the narrative (or narrator) prominently as a framework. He composed opening and closing choruses.

Bach and his contemporaries (and many who came afterward) provided examples of ways the oratorio form could stay true to itself at the same time it could be creatively expanded. Think Handel’s Esther or his Messiah (or any of his other 25 or so oratorios), Bach’s Christmas Oratorio, Mendelssohn’s Elijah. There was Telemann, Beethoven, Schumann, Elgar, Ralph Vaughan Williams and many others.

The oratorio form continues to be popular. Paul McCartney (Yes, that Paul of the Beetles) in 1991 wrote Liverpool Oratorio at the invitation of The Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra for their 150th anniversary. McCartney’s composition is a story that follows his own lifeline: school years, early career and marriage difficulties, ending with the birth of his first son. Liverpool Oratorio spent many weeks at the top of classical music charts worldwide.

In 2007 American composer David Lang composed The Little Match Girl Passion based on Hans Christian Andersen’s story of a poor little girl trying to sell matches on Christmas Eve, afraid to go home because her father will beat her for not selling enough. She dies while she is still on the street. Her grandmother comes to carry the little girl’s soul back with her to Heaven. Little Match Girl Passion has songs like “It Was terribly Cold,” “In An Old Apron,” “She Lighted Another Match,” “We Sit and Cry.” Lang won a Pulitzer in 2008 for The Little Match Girl Passion and a Grammy in 2010.

Craig Hella Johnson carries forward this long tradition in tonight’s oratorio.

Considering Matthew Shepard is an American contemporary fusion oratorio.

It is very American with its inclusion of blues, gospel, cowboy song, folk ballads, theater songs, jazz, country. It is very American in its location… the waving grasslands of wide Wyoming. It is very American in its central character, Matthew Shepherd. Though Matt knew five languages and had graduated from high school at The American School in Switzerland (his father Dennis worked as an oil industry safety engineer for Saudi Aramco), Wyoming was the place Matt was born and the place he thought of as home.

CMS is both American and contemporary in its subject matter. It is based on the true story of the death of 21-year-old Matthew Shepard in October 1998. Matthew was kidnapped, beaten, tied to a split rail fence of lodgepole pine, and left in a field near Laramie, Wyoming. He died six days later, never having regained consciousness. (In 2009 President Obama signed into law THE MATTHEW SHEPARD AND JAMES BYRD, JR., HATE CRIMES PREVENTION ACT.)

Tonight’s oratorio is also contemporary in its fusion of styles and elements of music. CMS follows the traditional passion oratorio structure: Prologue, Story of suffering and death (Passion), Epilogue. There is Narrative Text that outlines the story. Into this traditional framework Craig Hella Johnson has fused chants, cantor and audience response, simple songs, solo arias, trios, quartets, a turba chorus (voice of the people), a chorale. There are classical music and country. There are Gregorian chant and gospel hymns. There are drums and chimes and marimba, violins, cello, clarinet, viola, guitar, double bass, and piano.

The libretto or text of CMS is also a fusion. Craig and/or Craig and his co-writer Michael Dennis Browne have written the original pieces in the libretto. Craig has fused this original material with other borrowings into a libretto whole. There are the American poets John Nesbitt, Sue Wallis, Lesléa Newman, Michael Dennis Browne, and W. S. Merwin. There is the ancient voice from Genesis in the Hebrew Bible, Persian poets Rumi and Hafiz, Bengali poet Tagore, Dante and William Blake plus German poet, musician, artist, writer of medical texts, gemnologist, mystic, preacher, and advisor to Popes and Kings, Hildegard of Bingen. There are also the writings of Matthew Shepard himself. (You will hear several lines from Matt’s journals in the song “Ordinary Boy” and from Matthew’s mother, Judy and his father, Dennis.)

There is another way this is a very contemporary oratorio… contemporary as in right at this moment. We in the audience are invited to be participants in this story as it unfolds in tonight’s performance. Early in the Prologue, in a piece called “We Tell Each Other Stories,” we hear these words:

we tell each other stories so that we will remember… always telling stories… where and whom we came from… who we are…

This invitation for each of us to participate is very direct:

I am open to hear this story about a boy, an ordinary boy

Who never had expected that his life would be this story,

(could be any boy)

I am open to hear this story.

Open, listen.

All.

The first word sung in the oratorio is ALL. The title of the last movement of the oratorio is “All of Us.” WE are part of this story from the beginning to the end.

The Passion section of the oratorio uses four poems by Lesléa Newman as structural pillars for telling the story. In each of these poems the fence to which Matthew was tied speaks as if a person. There is “The Fence (before),” “The Fence (that night),” “The Fence (one week later),” “The Fence (after).” Other Newman poems are also part of the story. One of these is called “A Protestor.” The headnote for this poem refers to signs held by anti-gay protestors at Matthew Shepard’s funeral and the trials of his murderers. I’d like to look for a moment at the musical setting for this poem.

“A Protestor” is in the key of E-flat Minor. E-flat Minor is played all on black keys of the piano. Sound is prickly. Up on spears. The music opens with a call to arms. Here CHJ has chosen as a call to arms a direct quote of the opening bars of Benjamin Britten’s piece “This Little Babe” from his Ceremony of Carols. (Listen for these opening bars in the opening of a Conspirare recording of “This Little Babe” from their Christmas 2011 CD Something Beautiful.) In the original music that follows this call to arms the message of Britten’s words serve as inspiration: “… come to rival Satan’s hold… with tears he fights and wins the field…” which in turn sound out Britten’s source, 16th century poet Robert Southwell: “come to rifle Satan’s fold. All hell doth at his presence quake though he himself for cold do shake… the gates of hell he will surprise.” So while the protestors have their say in the words of the text, the music itself answers the taunting of the text: you will not break our spirit. We are fighting for Matt. The notes of this piece aim to provide musical protection for Matt. Even while the protestors yell, “The fires of hell burn hot and red/Beneath the Hunter’s Moon he bled/That must have been a pretty sight/The fires of hell burn hot and red”the music answers back… we’ve come to rival Satan’s hold… we’ve come to rifle Satan’s fold.

In a cacophony of words and sound in the piece “Fire of the Ancient Heart” (think drums and chants and outbursts and loud cries), we can begin to have some idea of the personal work it takes to rival and rifle wrong, loss, unfairness, those dark times in all of our lives. The voice of a cantor begins by asking “What have you done?” from Genesis. The choir sings, “called by this candle/led to the flame.” This movement allows us to relive our own experience of “being tried by fire” (and who amongst us has not been in such a fire). Voices sing the words of Rumi, “In each moment the fire rages, it will burn away a hundred veils” and William Blake’s “eyes of flesh, eyes of fire.” The use of percussion and repeated phrases and vocal intensity in this movement suggest a journey of alchemy. The experience of being put through a process where fire burns away the dross so that a substance can be transformed into its potential essence. The movement ends with the words, “Open us, All!” WE are still central in this story.

One of the Essential Questions of CMS is this: Can we look into the pain of senseless acts in the world around us and somehow, as we are asked in the oratorio’s Prologue,

try to find meaning in the living of our days… trying to find the meaning… ?

What meaning can we find in senseless acts of cruelty like the murder of Matthew Shepard, like scenes we witness every day in newspapers, online, and on television? In experiences we may have had in our own lives? Can we find any capacity for compassion?

In our story we have 5‘2”, 105-pound, 21-year-old Matt… passionate about human rights, University of Wyoming student representative to the Wyoming Environmental Council, a young man who wants to work for the US Diplomatic Corp when he graduates. We also have a Matt who wasn’t a perfect person. As his mother Judy said in an interview when the movie Matt Shepard Is a Friend of Mine was released, “As the years went on and our work continued, we began to notice that the Matt we knew was overshadowed by the idea of ‘Matthew Shepard’— he wasn’t a perfect person, he wasn’t an angel without flaws. Matt had struggles and hardships and successes like anyone else, which is really what made what happened so tragic.”

We also have Aaron McKinney and Russell Henderson who were arrested shortly after the attack and charged with murder, kidnapping, and aggravated robbery. Both McKinney and Henderson, each age 21, came from disadvantaged beginnings: Aaron’s parents divorced, his mother raised him, she died from a botched operation… he once attacked his mother’s doctor in a public place after her death. Russell’s teen-aged mother left him with his grandparents who raised him (he became an Eagle Scout and once had his picture taken with the Governor of Wyoming, was on the honor roll, and was a member of Future Farmers of America). His grandfather died when Russell was 15. He then became a young man without a shape for his life.

In the oratorio we are asked in three pieces that form a unit of sorts if we can identify with these young men in any way. Tagore’s words “stray birds of summer” are set in Gregorian chant providing a vision of young boys who have lost their way. A four-part male chorus muses in “We Are All Sons”: “if you could know for one moment/how it is to live in our bodies within the world.” “I am Like You,” a vocal quartet composed in minimalist style with vertical and horizontal spareness, asks us to consider: “Late one night I had a glimpse/of something I recognized, just a tiny glimpse/I don’t even like to say this out loud, it isn’t even all that true — but I wondered for a moment, am I like you?”

What sustains us as we live through a process of grappling with these hard questions?

Early in the oratorio, in the movement “The Fence (that night)” where the fence tells us about holding Matt all night — “he was heavy as a broken heart” – Hildegard of Bingen’s homage to the evergreen tree has been inserted:

Most noble evergreen with your roots in the sun; you shine in the cloudless sky of a sphere no earthly eminence can grasp… enfolded in the clasp of ministries divine… most noble evergreen tree.

This evergreen tree (and our evergreen hearts) appear and reappear in subsequent movements.

We are told in one of the narrations in the oratorio that Judy Shepard reported that the sheriff’s deputy who was first officer on the scene told her she saw a large doe lying near Matt — as if the deer had been there all night. In “Deer Song” a trio of sopranos, in wafting, floating voices that weave around and entwine, speak in the voice of the deer: “All night I lay there beside you, I cradled your pain in my care… welcome, welcome, sounds the song… always with us, evergreen heart.”

The setting that CHJ writes for Newman’s final fence poem, “The Fence (after)” uses the musical pattern ostinato (think of the word obstinate or stubborn) as the dominate style: a motif or phrase persistently repeats in the same musical voice, usually at same pitch (like a riff or a vamp in rock and jazz). Into this text, an excerpt from another Newman poem, “The Wind,” is inserted, ending what has been sparseness — 1 or 2 notes, phrases, sung into space in repeating patterns —

prayed upon

frowned upon…

adored

abhorred…

broken down

broken up —

with a lilting choral song,

The North Wind

carried his father’s laugh

The South Wind

carried his mother’s song…

Dennis Shepard’s statement to court identified the friends who were with Matthew while he was tied to the fence… the night sky with the stars and moon… the sun on a cool, wonderful autumn day, the ever-present Wyoming wind, the smell of sagebrush, scent of pine trees.

Creation holds us.

We are sustained.

We can walk to the fence in the movement “Pilgrimage” (with words reminiscent of the ancient Iris prayer St Patrick’s Breastplate also known as “The Deer’s Song”).

Beauty before me/beauty behind me/beauty above me/beauty below me…

And leave the fence surrounded by beauty

Sigh of sagebrush, hush of stone. Beauty above me, beauty below me, by beauty surrounded… wail of wind… cry of hawk.

And because of the possibility that creation does hold us and we are sustained, we can answer a question that comes at the turning point of the oratorio. In the aria, “In Need of Breath,” a voice representing Matt sings a Hafiz poem:

My heart is an unset jewel… I enter a realm divine… I too begin to sweetly cast light, like a lamp… through the streets of this World.

Matt Shepard, the boy, the son, now becomes Matthew Shepard, the iconic figure who can “cast light through the streets of the world.” This is the beginning of that enormous world-wide story. A story that says, “Don’t leave me here; bring the light. Bring an expanding heart.” The fence has been a witness. Can we ourselves be a witness with an evergreen heart? Can we “like a lamp… cast light through the streets of this world?”

In the title of the oratorio we have been asked to consider Matthew Shepard.

Consider: to think about carefully, care about, to see something as a possibility, reflect upon, deliberate about doing something or about whether to do something. The word consider comes from Latin and means to look up at the constellations, to look up at the stars. So to consider in its original form was to use our eyes. To look. To observe. To look at creation and take note of what we see.

The Epilogue begins. We have reached a new place. A place of hard-won wisdom… a place of clarity of vision… a place on which to stand. This is not a place of stoic resignation. It is not some version of flaccid acceptance. It is a place of personal strength and considered stance. Each in her or his own way. To whatever end… quiet or active… has reached a deeper truth, an expanded heart, an open future.

As the opening movement of The Epilogue reminds us in “Meet Me Here”:

Won’t you meet me here

Where the old fence ends and the horizon begins…

We are home in the mountain

And we’ll gentle understand

That we’ve been friends forever

That we’ve never been alone

We’ll sing on through any darkness

And our Song will be our sight

We can learn to offer praise again

Coming home to the light…

The first musical notes sounded in the oratorio were these from Bach’s Prelude #1 in C Major from The Well-Tempered Clavier Book I.[Notes played over loudspeaker] In the movement “Thanks,” which follows “Meet Me Here,” Craig Hella Johnson has returned to the Bach prelude as the foundation of this musical setting for Merwin’s poem. He inserts throughout the poem random versions of “thank you,” both for instruments and singers, including “thank you” in two Native American languages. These insertions of “thank you” are meant to sound as if they are spontaneous. A kind of “speaking in tongues,” “speaking in thanks.” All the universe in all forms is saying, “Thank you.” Irregular rhythms are mixed in 4/4 time. The Bach prelude, with the key of C Major in which it is written, suggests that all randomness and irregular rhythms can be held in this very stable form. We come back to wholeness, simplicity, completeness.

C Major is a “coming home” key. Bob Dylan calls it “a key of strength, but also the key of regret.” Some call it a simple serious happy key… no sharps and flats. (You remember that just a few days ago the sound of two black holes colliding a billion light-years away was heard and recorded… that sound — or chirp as the scientists called it — can be replicated by running your thumbnail from lowest note on the piano keyboard to… you guessed it… middle C. The chirp abruptly stops at middle C.)

Following “Thanks,” we hear a gospel piece “All of Us” ringing out:

Only in the love

Love that lifts us up…

Out of heaven, rain,

Rain to wash us free;

Rivers flowing on,

Ever to the sea;

Bind up every wound,

Every cause to grieve

Always to forgive,

Only to believe.

Embedded in this gospel piece is the tradition Chorale or Hymn of the oratorio. That chorale says:

Most Noble Light, Creation’s face,

How should we live but joined in you,

Remain within your saving grace

Through all we say and do

And know we are the Love that moves

The sun and all the stars?

The hymn is a simple, straight forward form. Sung homophonically — same text, same rhythm, a cappella. We’ve just been listening to a fusion of many styles and elements. Here the form is focused, structured. This movement says musically, “We are a choir. This choir is the people who have been expressing all these things in solos and trios and groups and sections. In arias and ballads, in phrases and refrains. Now we are a choir. A choir singing together this hymn.”

This choir, too, is all of us, as the title reminds us. We are the choir. While we express many manifestations in creation, we are also a collective voice. The first verse of the hymn is in B-flat Major; after the first verse the key changes to C Major. So we end where we began. We are in our coming home key again.

Then the reprise. The key is still C Major. The words that we heard at the beginning of the oratorio repeat:

(This chant of life cannot be heard

It must be felt, there is no word

To sing that could express the true

Significance of how we wind

Through all these hoops of Earth and mind

Through horses, cattle, sky and grass

And all these things that sway and pass.)

And, finally, the cowboy yodel that opened the oratorio sounds again:

Yoodle — ooh, yoodle-ooh-hoo, so sings a lone cowboy,

Who with the wild roses wants you to be free.

Enjoy the performance.

Thank you.

Dr. Elizabeth Harper Neeld